There are two related but very different concepts centered on the relationship between truth and humans that are frequently conflated. These frequently conflated concepts are ontology and epistemology.

There are two related but very different concepts centered on the relationship between truth and humans that are frequently conflated. These frequently conflated concepts are ontology and epistemology.

Ontology: This is the study of what exists. Ontological claims are either true or false. Either there are space aliens, or there are not. Ontological categories are the cleanly discrete two categories of true and false.

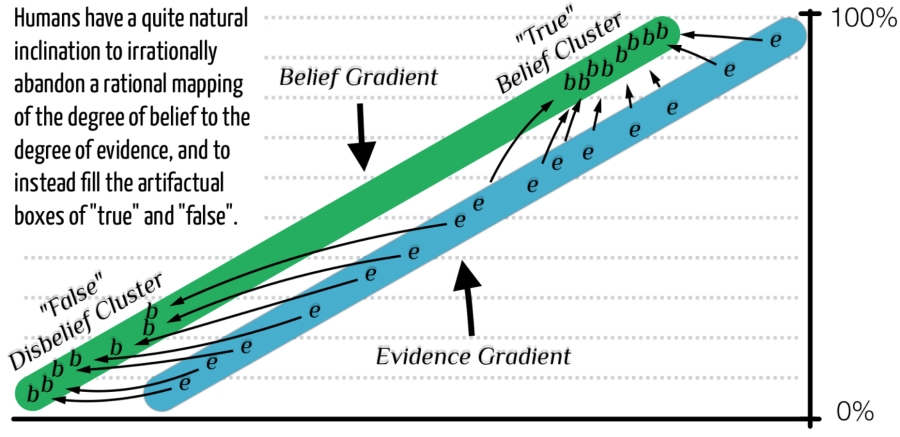

Epistemology: In contrast, when fallible, non-omniscient humans are assessing ontology their degree of certainty is not a binary and discrete categorization. Absolute certainty about the existence or non-existence space aliens is not justified since the confirming and disconfirming evidence for their existence arrives incrementally. Evidence for a proposition arrives in degrees, and therefore, the rational human will attempt to faithfully map their degree of certainty to the balance of evidence for the proposition.

Unfortunately, humans have a natural drive to epistemically categorize every claim as true or untrue. We are comforted by these discrete epistemic boxes we can neatly fit our beliefs into, even though these boxes are improper and artificial. This over-simplistic categorization makes the world feel far more manageable than if we had to map our degree of certainty to the ever-changing balance of evidence. More often than not, this human drive to discretely categorize our beliefs results in distorted and irrational certainties that irrationally tend towards the polar ends.

For example, if a romantic parter tells you they have been faithful to you, as a normal human, you may ignore evidence to the contrary until that evidence reaches an emotional threshold you can no longer ignore. Many individuals will, in this case, then flip their extreme belief in the claim of fidelity to extreme disbelief. Both the extreme belief and the extreme disbelief are irrational since rational belief will dynamically map to the up and down movements of the balance of evidence for that claim. The degree of belief moves with the unfixed degree of the evidence.

We also often disbelieve a claim until the incremental evidence reaches an arbitrary threshold at which point we flip our extreme disbelief to belief. Yet, for the rational mind, as incremental confirming or disconfirming evidence accrues, the degree of belief will follow smoothly up or down the epistemic gradient.

What is it that makes probabilistic assessments drift towards the pole of the epistemic gradient? We tend to either cleanly believe or cleanly disbelieve. We accept or reject a claim with little room for uncertainty.

The following are just a few terms that might reflect this tendency to invoke a subjectively determined epistemic threshold at which we either recategorize our belief to disbelief, or our disbelief to belief.

- X is [commonly known/a fact/proven].

- I have [certainty/confidence] that X.

- I [believe/accept/know] that X.

- X is [reasonable/sensible].

- The evidence for X is [convincing/persuasive].

- I am [convinced/certain/confident] that X.

- I will [persuade you to believe/convince you of/prove to you] X.

- We can [certainty/reasonably/confidently] conclude that X.

Why do our degrees of belief/disbelief on many of life’s propositions drift to and clutter at the extreme poles? Here are a few primary reasons.

1: Linguistic shortcuts are efficient. We regularly sacrifice semantic resolution for communicative brevity. The less the resolution of the concept is important to the communicative context, the more we abbreviate. This usually keeps dialogue smooth and efficient. The danger lies when we a) subtract out semantic resolution that is essential to the goal of the interaction, and when we b) begin to suppose that the linguistic shortcut for the quite nuanced underlying concept is somehow logically prior to that concept for which it was invoked to serve. The fact that the binary shortcut terms “belief” and “disbelief” have some utility in casual contexts that require little resolution in no way diminishes the intrinsic gradient nature of belief.

2: Life is more about binary decisions instead of gradient degrees of belief. Unless we can make decisive choices, life will pass us by. And decisions are largely binary. We choose to marry or stay single. We choose to accept or reject a job offer. This binary nature of decisions sometimes wrongly suggests to our minds that our probabilistic assessment of the outcome of our options must also be binary. And it is emotionally comforting to us when we conclude with high certainty that our choice was the best choice. We do this in violation of the actual degree of the degree of evidence at times. (See “Supplementary C”.) It could be argued that this violation of the evidential evidence is beneficial. If we choose to jump a chasm to escape an angry tiger, it may be advantageous to believe with full certainty we can jump that chasm. A degree of doubt that maps to the degree of the actual evidence may lead to less-than-desirable results. So perhaps our tendency to ignore less-than-certain evidence to arrive at an unwarranted certainty does have occasional survival advantages. Yet, self-delusion is no reason for the mind seeking increased rationality to avoid an honest attempt to reel in this tendency to abandon the nuanced balance of evidence.

3: Humans like order, and gradient concepts are messy. It may seems to us that the words “believe” and “disbelieve” reflect something essentially binary about the concept of belief. But these terms do not capture the actual intrinsic gradient nature of rational belief that makes decisions and assessments much messier. This becomes more apparent when we consider the words “like” and “dislike”. We know that, those these words are often conversationally presented as discrete opposites such as “full” and “empty”, there are intrinsically many degrees of like and dislike all along a single gradient. We have no problem taking ten random photos and ranking them in order of their aesthetic appeal. We recognize that “like” and “dislike” are merely linguistic shortcuts. Yet we somehow find it more difficult to do this with “belief” and “disbelief”, even when we acknowledge that the concept of belief is intrinsically gradient.

This same cognitive tendency to over-categorize our certainty into polarized boxes in distortion of the actual evidence is also reflected in the way we assess the qualities of objects and individuals. We speak of the “good guys” and the “bad guys” even though we know human character falls on a normal bell curve. We want to have clear demarcations for ethical dilemmas even though we know there are cases in which we are simply choosing the lesser of the two evils (“evil” is used colloquially here), each evil falling non-discretely somewhere on the gradient of harm that may be caused.

What is the take-away?

Linguistic terms must never supersede the concepts they are invoked to reflect. The fact that a couplet of polar terms such as “belief” and “disbelief” or “like” and “dislike” are neat linguistic boxes of over-simplification does not mean that the simplistic highly-pixelated low-resolution non-nuanced natures of these terms somehow informs us of the essence of the underlying concepts such as the gradient of belief or the gradient of liking. To tell someone “Either you believe me or you don’t” or “Either you like me or you don’t” is to improperly place language above concepts.

And this is the fundamental flaw of many religions. Many religions treat belief as something intrinsically binary, and they often pressure humans to violate the rational epistemic link to balance of evidence by conjuring up a degree of absolute or near-absolute confidence that violates the actual degree of the evidence. This willful violation of the degree of evidence is often called “faith”, and is repackaged as something virtuous. Faith of this sort is never virtuous. It is antithetical to rationality. Faith is illegitimate to those honestly committed to balancing their degree of belief to the degree of the evidence. These religions also absurdly depict doubt as a character flaw. (See #28.) Unless the objective evidence is at 100% certainty (and it never is for fallible minds assessing external phenomena), there is necessarily a degree of rational doubt for the honest mind. (See “Supplementary H”)